We all consider it normal now—women voting, running for office, having a voice in democracy. It's so fundamental that we rarely stop to think about it. But this right wasn't freely given. It was fought for, bled for, and in some cases, died for.

The women who waged that fight were called suffragettes. Their story is one of remarkable courage, strategic brilliance, and radical sacrifice. And it offers a powerful lesson for any woman today who has ever been told to sit down, be patient, or wait her turn: sometimes, the only way forward is to demand what you deserve.

When Polite Requests Weren't Working

Women in Britain had been campaigning for the right to vote since at least 1865. For decades, they used peaceful, "respectable" methods—writing letters to MPs, presenting petitions to Parliament, making reasoned arguments. They were called suffragists, and they believed that if they proved themselves worthy, the men in power would eventually extend them the vote.

It wasn't working. Decade after decade, nothing changed. Women remained voiceless in a democracy that claimed to represent them.

By the early 1900s, a new generation of women was losing patience. Among them was Emmeline Pankhurst, a widow and mother who had spent years watching polite activism achieve nothing. In 1903, she and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester. Their motto was blunt: "Deeds, not words."

The term "suffragette" was actually coined by the Daily Mail in January 1906, intended as mockery—a diminutive, dismissive label for these troublesome women. But the women of the WSPU embraced it. They wore the insult as a badge of honor.

The Night Everything Changed: Manchester, 1905

The suffragette movement as we know it began on a single October night in 1905 at the Manchester Free Trade Hall.

Christabel Pankhurst, then 25 years old, attended alongside Annie Kenney, a mill worker from Oldham who had started working in textile factories at age 10. The two women had a plan. During a Liberal Party rally featuring Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, they would ask one simple question: "Will the Liberal government give votes to women?"

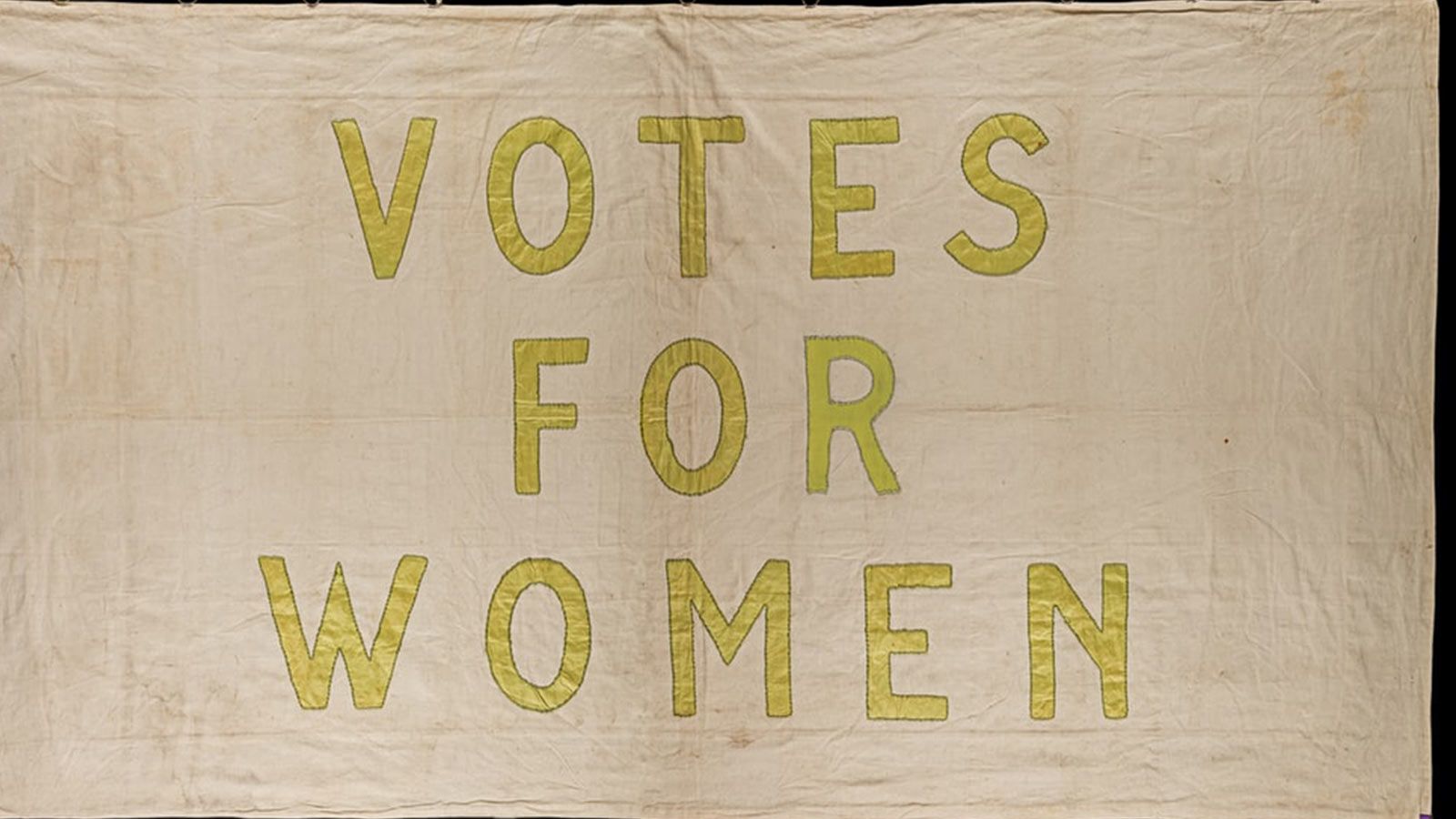

They were ignored. They asked again. Still ignored. They unfurled a banner reading "Votes for Women" and kept shouting. They were thrown out of the hall and arrested—Christabel for allegedly spitting at a police officer (she later said it was more of a "pout"), Annie for obstruction.

Given the choice between paying a fine or going to prison, both women chose prison.

It was the first time women had been imprisoned for campaigning for suffrage in this way. The newspapers exploded with coverage. And suddenly, everyone knew who the suffragettes were.

Annie Kenney later wrote to her sister from prison: "You may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways yesterday morning. There were over one hundred people waiting." The movement had found its spark.

From Marches to Militancy

In their early years, the WSPU organized massive demonstrations. In June 1908, seven different marches converged on Hyde Park, bringing together an estimated 300,000 people—one of the largest political gatherings Britain had ever seen. The message was clear: this wasn't a fringe cause. It was a movement.

But the government still refused to act. And then came Black Friday.

On November 18, 1910, a peaceful deputation of suffragettes approached Parliament. Police were ordered to push them back—and the violence that followed was shocking. Women were punched, kicked, groped, and beaten for six hours. Many of the assaults were sexual in nature. Over 100 women were injured.

The survivors asked Emmeline Pankhurst a devastating question: What was the point of suffering this brutality in peaceful protest, when smashing a window would result in a quick arrest without physical assault?

The calculus shifted. Starting around 1912, suffragette tactics escalated dramatically. They chained themselves to railings. They smashed windows across London's West End. They slashed paintings in galleries. They cut telegraph wires. They set fire to empty buildings and postboxes. They planted bombs.

Christabel Pankhurst justified the tactics in WSPU pamphlets: "The reformer breaks the law... for the salvation of our State." Throughout the campaign, both she and her mother emphasized that there should be no danger to human life. Their targets were property and disruption, not people.

It was a calculated risk—and it worked. The government could no longer ignore them.

The Price They Paid: Prison, Hunger Strikes, and Torture

Over a thousand suffragettes were imprisoned in Britain. Many, including Emmeline Pankhurst herself, went on hunger strikes to protest their treatment and draw attention to the cause.

The government's response was force-feeding—a brutal procedure that amounts to torture. Prison doctors would pry open a woman's mouth with a steel gag, insert a tube down her throat or nose, and pour liquid food directly into her stomach. Women vomited, bled, and sometimes aspirated food into their lungs.

Sylvia Pankhurst described the experience in a letter: "I am fighting, fighting, fighting. I have four, five, and six wardresses every day, as well as the two doctors. I am fed by stomach-tube twice a day. They prise open my mouth with a steel gag, pressing it in where there is a gap in my teeth. I resist all the time. My gums are always bleeding."

Public outrage over force-feeding eventually forced the government to change tactics. In 1913, they introduced the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act—quickly dubbed the "Cat and Mouse Act." It allowed authorities to release hunger strikers when they became dangerously weak, then re-arrest them once they recovered. The cycle of arrest, hunger strike, release, and re-arrest was designed to break the women without creating martyrs.

Annie Kenney was imprisoned 13 times. She became one of the most wanted "mice," spending months evading police while continuing to organize. When Christabel fled to Paris in 1912 to avoid conspiracy charges, Kenney essentially ran the WSPU's operations in Britain—a working-class mill girl leading one of the most radical political movements in the country.

The Ultimate Sacrifice: Emily Davison

On June 4, 1913, Emily Wilding Davison walked onto the track at the Epsom Derby as King George V's horse Anmer rounded Tattenham Corner. She was struck by the horse and died four days later.

Davison was carrying a suffragette banner. Whether she intended to attach it to the horse's bridle as a protest or meant to die remains debated by historians. What is certain is that her death sent shockwaves through Britain and beyond. Her funeral procession through London drew massive crowds.

Emily Davison had been imprisoned nine times, force-fed 49 times, and had once thrown herself down an iron staircase in prison to protest the treatment of suffragettes. She gave everything she had—including her life—to a cause she believed was worth dying for.

War, Work, and Victory

When World War I broke out in 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst made a strategic decision that surprised many: she called for a pause in suffragette militancy to support the war effort. It was controversial—some suffragettes, including Sylvia, refused to stop fighting—but it proved to be a masterstroke.

With men at the front, women stepped into roles they had been told they couldn't handle. They worked in factories, drove ambulances, managed farms, and kept the economy running. They proved—on a scale impossible to ignore—that they were capable, competent, and indispensable.

The combination of decades of activism, visible sacrifice, and undeniable wartime contribution finally broke the political deadlock.

On February 6, 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted voting rights to women over 30 who met property qualifications. It wasn't equality—men could vote at 21 with no property requirement—but it was a victory. About 8.4 million women gained the right to vote.

Later that year, women gained the right to stand for Parliament. And in 1928, the Equal Franchise Act finally granted women the vote on the same terms as men. Emmeline Pankhurst died just weeks before it passed, but she lived to know it was coming.

What the Suffragettes Teach Us Today

The suffragettes' story isn't just history. It's a blueprint for anyone fighting for change in a world that would prefer they stay quiet.

They teach us that progress isn't given—it's demanded. For decades, women asked nicely for the vote and were ignored. Change came when they stopped asking and started insisting.

They teach us that strategy matters. The suffragettes knew when to protest and when to pivot. They understood public relations, media attention, and political pressure. They weren't just brave—they were smart.

They teach us that setbacks are part of the journey. The Cat and Mouse Act, the ridicule in the press, the prison sentences—none of it stopped them. They treated every obstacle as another reason to keep fighting.

And they teach us that coalition matters. The movement included aristocrats and mill workers, mothers and young women, moderates and radicals. They didn't always agree on tactics, but they shared a goal.

Your fights today may look different—equal pay, flexible work, a seat at the leadership table, respect in a male-dominated industry. But the courage and conviction required to win them are the same. When you speak up in a meeting where you're the only woman, when you negotiate for what you're worth, when you refuse to accept "that's just how it is"—you're standing in a tradition that includes Emmeline, Christabel, Annie, Emily, and thousands of other women who refused to be silent.

Nothing is given. Everything is earned. The suffragettes knew that. And now, so do you.

FAQs About the Suffragettes

What is the difference between suffragettes and suffragists?

Suffragists were campaigners for women's voting rights who used peaceful, constitutional methods like petitions and lobbying. Suffragettes, specifically members of the WSPU, used militant tactics including civil disobedience, property destruction, and hunger strikes. The term "suffragette" was originally coined as an insult but was embraced by the militants as a badge of honor.

Why were suffragettes called suffragettes?

The Daily Mail coined the term "suffragette" in 1906 as a diminutive, mocking term for the women of the WSPU. Rather than reject the label, the women embraced it, turning an insult into a rallying cry.

How did the suffragettes protest?

Suffragette tactics evolved over time. Early methods included heckling politicians, marches, and demonstrations. Later, they escalated to window-smashing, arson of empty buildings, cutting telegraph wires, chaining themselves to railings, and hunger strikes in prison. Their motto was "Deeds, not words."

When did women get the right to vote in Britain?

Women over 30 who met property qualifications gained the vote in 1918 through the Representation of the People Act. Full equal voting rights—women voting on the same terms as men at age 21—came in 1928 with the Equal Franchise Act.

Who were the key leaders of the suffragette movement?

Emmeline Pankhurst founded the WSPU and was its most visible leader. Her daughter Christabel was the chief strategist. Annie Kenney, a working-class mill worker, became one of the movement's most prominent organizers. Emily Davison became a martyr when she died after being struck by the King's horse at the 1913 Derby.

What was the Cat and Mouse Act?

The Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act of 1913, nicknamed the "Cat and Mouse Act," allowed authorities to release hunger-striking prisoners when they became too weak, then re-arrest them once they recovered. It was designed to prevent suffragettes from dying in prison and becoming martyrs while still punishing them.

Related Reading:

• Emmeline Pankhurst: A Champion of Women's Suffrage

• How Gender Affects Communication at Work

• How to Ask for What You Want at Work

Sources:

• London Museum - Christabel Pankhurst: Suffragette Leader

THE WORKING GAL

THE WORKING GAL